Guide to Lower Body Pain Causes: Muscle, Posture & Prevention

How to Use This Guide: Outline, Scope, and Why Lower Body Pain Matters

Lower body pain affects how we move, work, rest, and play. It can be a whisper after a long walk, a shout after sprint repeats, or a nagging tightness that shows up every afternoon at your desk. This guide unpacks the common muscular and postural causes, compares how different problems feel, and shows practical strategies to reduce risk. Think of it as a map: we’ll name the landmarks (muscles, joints, movement patterns) and offer routes that help you get where you want to go with less discomfort.

Outline of this article:

– Section 1: Why this topic matters and how to navigate the guide.

– Section 2: Muscle mechanics—how soreness differs from strains and tendinopathy, and what symptoms usually reveal.

– Section 3: Posture and movement—how sitting, standing, walking, and foot mechanics shape stress on hips, knees, calves, and the low back.

– Section 4: Prevention in practice—strength, mobility, load management, recovery, and daily habits.

– Section 5: When to seek help, a simple decision pathway, and final takeaways tailored to everyday movers.

Why this matters: large surveys show that most adults experience low back or lower limb pain at some point, and recurring aches can limit activity, sleep, and mood. The good news is that many cases relate to modifiable factors—how we load tissues, how fast we progress training, and how long we hold certain postures. This guide focuses on actionable steps, while recognizing that some symptoms require clinical care. You’ll find clear explanations, examples you can picture, and checklists you can use immediately.

Before diving in, a few compass points:

– Pain is information, not a verdict. It often signals that a tissue or pattern needs a change in load, not that something is “broken.”

– Context matters. The same ache can mean different things depending on timing, intensity, and what preceded it.

– Progress is rarely linear. Expect small experiments—adjusting one variable at a time—to lead you toward steadier comfort and capacity.

With that, let’s explore the difference between muscle soreness and injury, then connect posture and movement to what you feel from hip to heel.

Muscle Mechanics: From Microtears to Strains and Tendinopathy

Muscles are brilliant adapters. They respond to demand by becoming stronger, more coordinated, and more efficient at sharing load with neighboring tissues. But adaptation requires a balance: too much, too fast, or too often can tip a helpful training stimulus into pain. Understanding what you’re feeling—delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), a strain, or a tendon issue—helps you adjust without overreacting or ignoring warning signs.

DOMS is the familiar stiffness and ache that peaks 24–72 hours after unaccustomed or high-volume work, especially eccentric loading (think downhill hiking, step-downs, or lowering a weight). It tends to feel diffuse, symmetrical in trained areas, and improves with light movement. By contrast, a strain is a discrete injury to muscle fibers, often triggered by a sudden, forceful effort (like an explosive sprint or a quick change of direction). Strains usually present as a sharp focal pain at the moment of injury, followed by tenderness, possible bruising, and pain with stretch or strong contraction.

Tendinopathy (often called “tendon pain”) involves the tissue that connects muscle to bone. It can begin with a dull ache during or after activity and progress to morning stiffness or pain with first steps. Common spots include the Achilles, patellar tendon below the kneecap, and the gluteal tendon near the outer hip. Unlike DOMS, tendon pain may ease as you warm up but return after activity or the next day; unlike strains, it typically develops gradually.

Practical distinctions at a glance:

– DOMS: diffuse soreness, predictable after novel load, improves with gentle movement.

– Strain: pinpoint pain, onset with a specific moment, hurts with stretch or resisted contraction.

– Tendinopathy: activity-linked ache or stiffness, better with controlled loading over time, aggravated by rapid spikes in volume.

Muscle groups commonly involved in lower body pain include:

– Glutes: weak or under-recruited gluteals can shift load to the low back or lateral hip.

– Hamstrings: tightness or previous strain can show up during acceleration or late swing in running.

– Hip flexors: prolonged sitting can make them feel short, changing pelvic position and stressing the low back.

– Calves: responsible for propulsion and shock absorption; when overloaded, the Achilles or plantar tissues protest.

Careful loading is powerful medicine. Most muscle and tendon pain responds to a blend of relative rest (reducing aggravating intensity), graded strength work (progressively heavier or harder, not necessarily more frequent), and movement variety. Heat or light aerobic activity can ease DOMS; structured strengthening and tempo control help tendinopathy; and early, gentle range of motion with gradual strengthening supports strain recovery. When in doubt, dial back the provoking variable—speed, incline, depth, or volume—before abandoning the movement entirely.

Posture, Alignment, and Movement Patterns: What Your Body Is Telling You

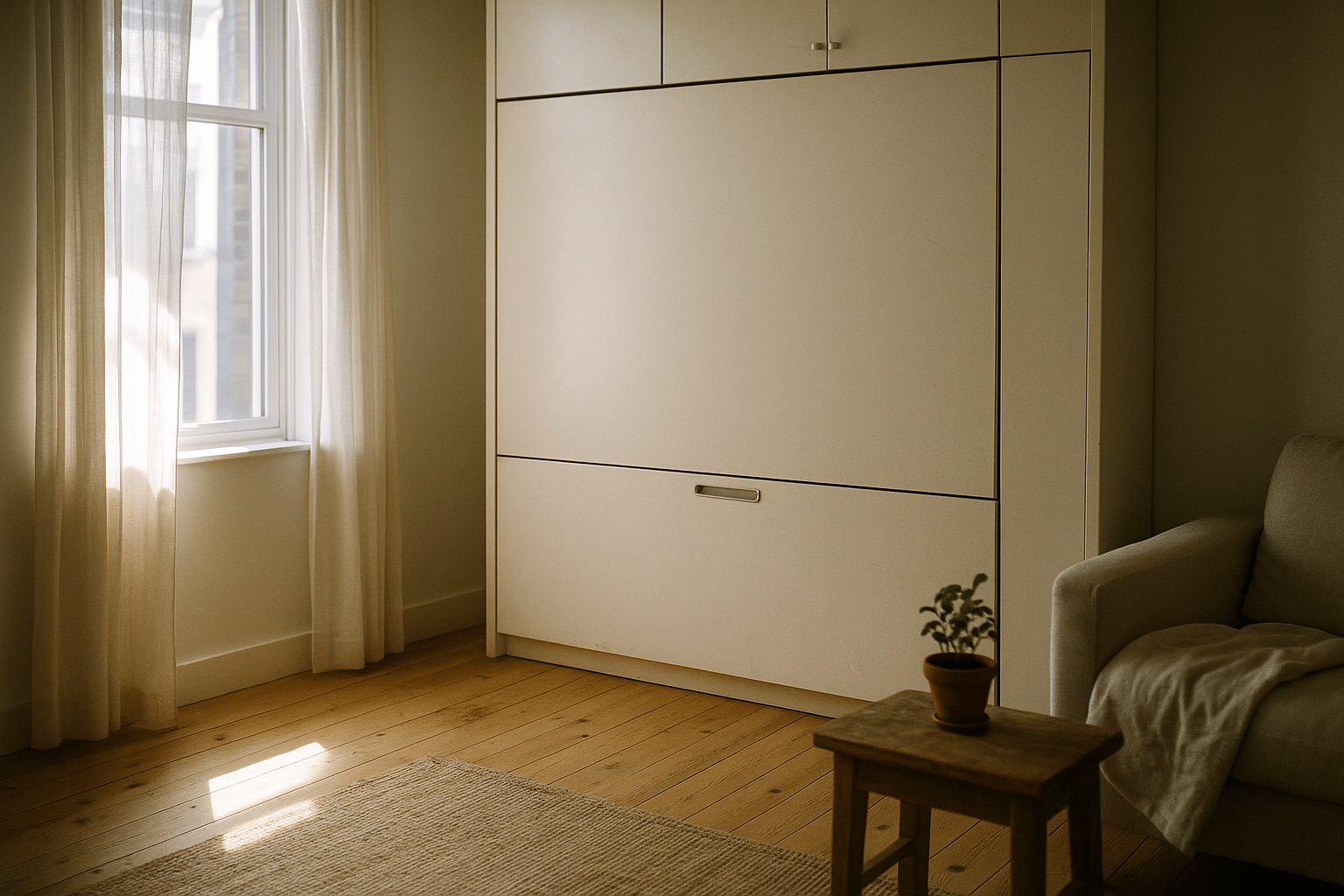

Posture is not a frozen pose; it’s a moving target. The positions you spend the most time in shape how tissues feel. Sitting, for instance, is not the villain, but uninterrupted sitting can set the stage for hip flexor tightness, reduced glute activation, and a cranky low back when you finally stand. Standing all day has its own issues: calf and foot fatigue, lumbar compression from sway-back tendencies, and hip discomfort if weight is habitually shifted to one side.

Common posture and movement contributors:

– Long sitting stints: hips flexed, glutes “offline,” thoracic slumped—later, the first steps after standing feel stiff.

– Prolonged standing: pelvis drifts forward, knees lock, calves work overtime to stabilize.

– Gait habits: overstriding increases braking forces at the knee and hip; short, quick steps can reduce impact.

– Foot mechanics: very flat or very high arches can redistribute forces; neither is “bad,” but both benefit from appropriate loading and footwear fit.

– Lifting patterns: bending at the spine under heavy load repeatedly can irritate tissues that prefer shared work with the hips.

Instead of chasing a “perfect” posture, aim for posture variability. Alternate positions and change the way load travels through your body. At a desk, think of your setup as a dynamic workstation rather than a fixed throne:

– Keep the screen at eye height to reduce neck strain and mid-back slump.

– Place the keyboard close enough to avoid reaching and shoulder elevation.

– Use a chair that lets your feet find the floor and your hips and knees stay near 90 degrees.

– Set a timer every 30–45 minutes for a brief movement snack: stand, reach overhead, march in place, or do calf raises.

When walking or running, imagine your body as a spring. Shortening your stride slightly and leaning just a touch from the ankles (not the waist) can reduce braking and knee stress. Think “quiet feet” and “soft landings” to nudge cadence up naturally. For lifting, rehearse the hip hinge: unlock knees, send hips back, keep the torso long, and let the glutes and hamstrings share the work with the spine. Start light, own the pattern, then layer load.

Two telltale signals your posture or pattern needs a tune: pain that builds the longer you hold one position, and relief that arrives with simple movement. That feedback is permission to vary, not a mandate to avoid. With practice, your setup and technique become levers you can pull to change the way your lower body feels—often within minutes.

Prevention That Sticks: Strength, Mobility, Load Management, and Recovery

Prevention is less about bubble-wrapping your body and more about teaching it to handle a wide range of loads. The lower body appreciates a trio of ingredients: strength to share forces, mobility to access positions comfortably, and pacing to keep tissues adapting instead of rebelling. Done well, these pieces build steadiness you can feel in daily life—on stairs, during long walks, and through workouts that once felt intimidating.

Strength that pays dividends:

– Hips: hip hinge (deadlift variations), split squats, and lateral movements train glutes and hamstrings to handle load without overreliance on the low back.

– Knees: controlled squats and step-downs teach the quadriceps to brake and propel safely.

– Calves and feet: calf raises (straight and bent knee), tiptoe holds, and short-foot drills improve push-off and arch support.

– Core: anti-rotation and anti-extension work (pallof press, dead bug patterns) stabilize the trunk so limbs can generate force efficiently.

Mobility to unlock comfortable ranges:

– Hips: 90/90 rotations, hip flexor glides, and deep squat prying ease stiffness from sitting.

– Ankles: kneeling dorsiflexion rocks and gentle calf stretches improve stride mechanics and squat depth.

– Thoracic spine: open-books and child’s pose side reaches help the upper back share motion with the low back.

Load management rules of thumb:

– Progress one variable at a time—either volume, intensity, or complexity—not all three in the same week.

– A conservative weekly increase (for example, around ten percent) helps tissues adapt, especially when returning from time off.

– Alternate harder and easier days; your nervous system and connective tissue thrive on rhythm, not constant redline efforts.

Recovery is the glue:

– Sleep sets the stage for tissue repair and pain modulation; aim for a consistent schedule and a cool, dark room.

– Nutrition and hydration support adaptation; regular protein intake and fluids throughout the day can help you feel more resilient.

– Active recovery—easy cycling, walking, mobility flows—keeps blood moving without adding stress.

Micro-habits multiply over time. Add five-minute movement breaks between meetings, stand on one leg while brushing teeth, or finish a workout with two calm breaths per rep to downshift the nervous system. Prevention isn’t a grand gesture; it’s a string of small moves that teach your body to carry you comfortably across the week.

When to Seek Help, Self-Care Next Steps, and Final Takeaways

Most lower body aches improve with smart adjustments. Still, certain signs call for timely evaluation. Red flags include:

– Significant trauma followed by inability to bear weight.

– Progressive weakness, numbness, or leg heaviness that doesn’t improve with gentle movement.

– Unexplained fever, night sweats, or unintentional weight loss accompanying pain.

– Pain that wakes you nightly or steadily worsens despite reducing load.

– Calf swelling, warmth, and tenderness after prolonged immobility or travel.

If none of the above apply, try a simple decision path over 10–14 days:

– Step 1: Identify the aggravator (speed, incline, depth, impact, duration). Reduce or pause the most provocative element, not the entire activity if possible.

– Step 2: Add gentle movement that feels good—easy cycling, walking, or range-of-motion drills.

– Step 3: Introduce targeted strength for the area just upstream and downstream of the pain (for knee aches, think hips and calves; for Achilles, include calf and foot strength).

– Step 4: Re-test the original activity in smaller doses; keep what feels neutral or better, remove what spikes symptoms.

– Step 5: If pain remains high or function stalls, book a personalized assessment.

Closing thoughts for everyday movers: lower body pain is a conversation between tissues and tasks. Muscles and tendons don’t complain at random; they react to how you load them, how often you rest, and how consistently you build capacity. Use this guide to experiment—small, patient changes often beat heroic overhauls. Vary your posture, respect early warning signs, and let strength work be the steady drumbeat in your routine. And remember, confidence grows alongside capacity: the more you understand what you feel and why, the easier it becomes to choose the next right step.